I said it. Students heard it. Students will remember it. Not really. Educators assume or expect students to remember, but assumptions are not facts. Remembering what a teacher said is a struggle between working memory and brain dumping. If there is not an overt effort to retain what is heard, seen, or perceived, the working brain will dump what was heard, seen, or perceived within 30 seconds. That is a fact. A teacher who wants children to remember what they have been taught must know and practice principles of retention theory. If not, teaching is a wind that blows through children’s minds leaving little that was learned.

What do we know?

Retention is the unspoken assumption in everything we do in school. We want children to remember what we teach them. We test the heck out of students as an assurance that they remember their instruction. We reward children with high test scores and create tiers of intervention and remediation for children with low test scores. Test scores have become our measurement of retained memory. In fact, this pathway almost ensures that instructed learning will not be retained. It is based on false principles and practices.

Let us remember what we know about remembering.

- The brain is bombarded with thousands of words, images, sounds, and perceptions every hour. The brain is not designed to and will not remember every input it receives.

- If the brain does not consider/mentally repeat a word, image, sound, or perception it is lost within 30 seconds. The 30-Second Rule is reality.

- The brain considers to seven to ten bits of information at a time – there is a constant pass through of information in immediate recall. The 30-second rule constantly moves the brain to “next” and “next.”

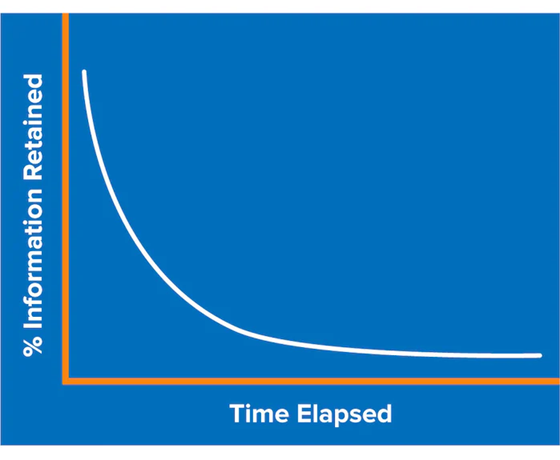

- The Forgetting Curve also is a natural function of the brain’s need to be moving on to what is next in life. We forget 50% of received information within one hour and 70% within 24 hours without overt actions to reinforce the retention of that information.

Humans innately forget. If we want to students to remember, we must overtly use practices that cause them to remember. Retention theory must be embedded in every instructional lesson and unit.

Retention Theory

Madeline Hunter named five principles that cause students to remember instruction.

Meaning. One way to combat the 30-Second Rule is to make unfamiliar information meaningful. Brain retention improves when it knows that unfamiliar information connects to what a student already knows or the student’s personal interests. Personal interest is huge in reinforcing memory. She called these connections “anticipatory sets” or ways to overtly move the student toward a positive anticipation about a new lesson. This prepares the brain for memory.

Feeling Tone. Every classroom involves emotional theater, and teachers set the positive, negative, or neutral vibe in which teaching and learning happens. A teacher who has skills of affective and behavioral empathies creates a warm, inviting, and positive atmosphere. The lack empathetic skills and teacher-dominated class time builds hesitant, non-participative student responses in a negative climate. Positive and negative feeling tones are real – teachers know it when they are in one or the other, but do not always know their causations. A neutral feeling tone arises when there is a perceived indifference to whether children learn or not.

Degree and accuracy of Initial Learning. Both correct and incorrect learning lead to memory. Correct learning can be reinforced leading to long-term memory. However, incorrect learning needs to be identified, eliminated, and replaced with correct learning. Although interventions are required, they cloud reinforcement as the brain processes incorrect information out and correct information in. Therefore, when teachers take time to ensure all children achieve high levels of understanding of new instruction before moving to independent practice, teachers are enhancing memory work and retention.

Practice Schedule. Practice does not make perfection, it makes permanence. Theories show that massed practice or “cramming” is effective for fast learning that leads to quick forgetting. In contrast, distributed practice episodes are the key to long-term retention. Practice in retrieving remembered information builds memory muscle and intervals between practice sessions build permanence.

Transfer. The goal of teaching and learning is knowing things that are worth knowing and that can be applied in various new ways, places, and times. Retention of prior learning is reinforced when it is recalled and used in new contexts, and new learning is better understood and remembered when new memories are extensions of older, successful memories. Transfer that connects learning connects memories.

What to do. Each of the following describes a strategy for building and reinforcing retention based upon retention theory.

- Make information “sticky” and easier to remember. Information is not created equally. Some seems slippery and is hard to remember while other information, like tree sap that clings to fingers, seems sticky and is easier to remember. These strategies make information sticky.

Chunk it. Individual bits of information are hard to remember, but easier when chunked in meaningful groups or sequences or patterns. Chunking means remembering all the individual bits as one – it is easier to remember.

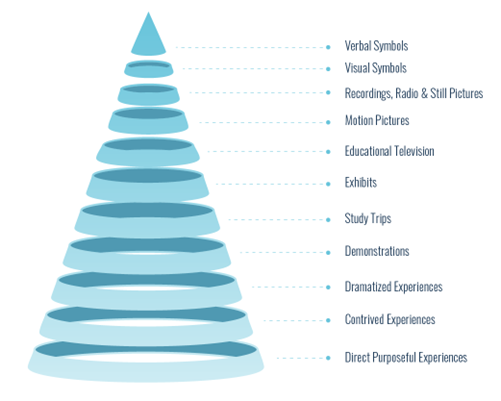

Show it. Research shows that human memory of images is better than memory of independent text or audio. A picture, a video, or a graphic gives the brain another dimension of unfamiliar information. The student sees the word and an image of the word or picks up a representation of the word. Things that can be handled and made tangible, are very memorable.

Add emotional or novelty context. The easiest emotions to embed in new learning are surprise, happiness, and fear. Children love things that go “bang” or have surprise endings. They associate the surprise and the information. All learners appreciate novelty – new things to experience. Just saying “You are the first students to …” makes whatever it is they do “sticky” in their memory.

Do it. Motor skills and experiences are stored in different areas of the brain from information. Teaching about graphing coordinates in math class creates information. Creating a grid on a soccer field and placing/locating things by their coordinates creates a know it/do it combination that is very sticky.

Conversely, there are ways to make information slippery and hard to remember. Avoid or eliminate slippery practices, like giving students lists of random numbers or facts to remember without any context for their memory, allowing passive listening without note taking or required verbal engagement, or giving students information that is highly similar/almost identical to prior information.

- Use active not passive retrieval of information. Memory requires mental activity and working the information until it avoids the brain dump, becomes short-term memory, then long-term memory, and is transferred to give meaning and context to other information. Passive retrieval relies on a student’s initial interaction with the information and rereading or repeating the same initial interaction. Passive retrieval yields low grade memory retention and leads to very quick forgetting.

What Did You Miss? After first instruction, ask students to write all they know about what they learned. Allow ten minutes. This on-demand retrieval exposes what the student remembers and, when compared with the totality of the first instruction, what is missing.

Discriminating Retrieval. Give students an explanation of the first instruction but one that is missing some information. Ask students to fill in the missing information. This retrieval requires to brain to “work” to clinically retrieve, consider, and identify the parts of the information.

Practice testing and retesting. The strategy of pre-testing and post-testing most often are used to inform and assess instruction. Pre-testing and subsequent testing also work to build and reinforce memory. In any test, students reinforce what they correctly remember. Testing strengthens successful memory retrieval.

Feedback loops. Testing also provides feedback about what students do not know. Focused work on improved reading, listening, seeing, and experiencing of unknown or non-secured information builds new memories. The active work needed to correct misinformation and learn correct information mentally strengthens memorization of what is learned.

Mental refinement/teach back (Feynman Technique). One of the most active is also the strongest retrieval strategy. When students teach what they learned to others, they must consolidate and refine the information they know, construct it in their own words, and deliver the information in ways the others can learn. We often hear that the best way to learn something is to teach it; that also applies to memorization.

- Spacing. The term “spacing” tells us that productive, active retrieval must is purposefully distributed not massed.

Intervals. Research suggests these intervals for moving new information into short-term memory and short-term memory into long-term. First review = 24 hours after first instruction. Remember: Without active retrieval, 70% of first instruction is forgotten in 24 hours. Second review = one week later. Third review = one month later. Fourth review = 3-6 months later.

10-30% Rule. Research recommends the optimal gap between retrieval/practice sessions should be 10-30% of the time you want students to remember the information. If the final test is in one month, use practice exercises every 3 to 6 days. If the final test or performance is in one year, practice once each month. For classroom rules that cover a school year, test/practice every month of the school year.

Interleaving. Do not practice the same information/skill at every practice session. Test/practice just a part of the same information at one session and other parts at subsequent sessions. And include different types of information in each session. This requires students to mentally sort through the memory, mine that information, and retrieve specific memories.

Leitner or Box Method. Everyday include a brief retrieval of new information and things students are having difficulty remembering. Every 3 days include a retrieval of things students are shaky on in their memory. Once every week practice information all students can retrieve easily.

- Layered mastery. Best practice is not the constant use of one active retrieval strategy. Like physical exercise, using one strategy repeatedly only makes that one type of memory stronger. Layered mastery creates a multi-month schedule of intervals for brain dumping, testing, teaching to others that causes students to retrieve information repeatedly, analyze the information, apply the information, evaluate the reliability and validity of information, and synthesize the information into new configurations. When teachers use Bloom’s Taxonomy to guide their use retention theory, they cause students to build their own retrieval systems.

The Big Duh!

The industrial model of teaching and learning in the United States makes curriculum a conveyor belt of information that teachers teach, and students try to learn. The high demands and constancy of our K-12 curriculum delivery do not include time and resources for meaningful information retention. We teach and test then teach and test something new. If we want students to know what they learn for more than one day or until the next quiz, we must understand and use retention theory and its research-based practices. If we do not teach students to build memory building and retrieval, we truly institutionalize forgetting.