Tested practices created from research-based theories give teachers the best instructional opportunities to cause all children to learn.

It is easy to think of teaching and learning as linear. We teach and children learn one thing then another and another. Learning is an additive like train cars on a railroad line running through a classroom. Each car arrives with facts and skills to be taught and learned before it leaves the classroom/station, and the next train car of facts and skills arrives. There is more truth in this analogy that teachers want to admit. We change this perception with one word – “so.” All a teacher needs to do to move teaching and learning from a linear to a geometric design is to ask “So, what can/will/should you …” and teaching and learning launch vertically from children waiting for the next lesson to children doing higher orders of cognition with what they have already learned. It is blooming wonderfully!

What do we know?

The names of historic education and psychology theoreticians are fixed in our teacher preparation programs. Their names appear in texts and as footnote references. Piaget, Dewey, Vygotsky, Montessori, Skinner, Bruner, et al. Teacher licensing candidates learn to pair a name with a concept the historic person developed, take a test or write a paper acknowledging that person’s name and concept, and then allow the forgetting curve to move the name and theory into their memory fog. Who was that? What theory?

Stop doing this! Teaching and learning theories matter because theories give us road maps for how to transform schooling from linear – learn to test- to geometric – learn to think and do.

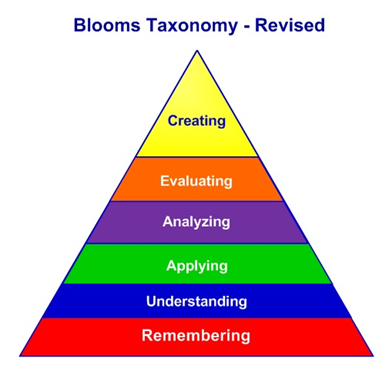

Benjamin Bloom, psychologist and pedagogue, gave us a systematic template to describe, assess, and classify educational goals. Bloom published his Taxonomy in 1956 and for decades teacher preparation schools taught Bloom’s cognitive domain, and six levels of cognition often called higher order thinking skills. Seventy years later, Bloom is still the go-to resource for describing and detailing levels of cognitive goals.

“So,” elevates your teaching and student learning.

The baseline of Bloom’s Taxonomy is the teaching and learning of background knowledge and a basic understanding of that knowledge. All children need to learn words that name and describe things in their world. So, we teach them to read and listen and build working vocabularies. Bloom categorizes the first goals of learning as level 1 – remembering and level 2 – understanding. A great deal of PreK-, 4K, and kindergarten involves experientially exposing children to words and facts and remembering and understanding.

In his research for his studies, Bloom saw that most classroom instruction at many grade levels was at level 1 and level 2 goals. Teachers used direct instruction to teach information for children to remember and describe. Teachers tested children, recorded learning scores, and began teaching the next lesson of information to be learned. Teaching and learning bobbled back and forth between remembering and understanding.

Bloom changed the goals of learning by interjecting “so what” into teaching. “So, what can you do with this information?” “So, how is this information like or unlike other information?” “So, which is a better choice in the use of this information?” And “So, what could you create from this information that is new and different?” Each of these questions is indicative of a higher level of cognition requiring children to think differently to answer the question. Bloom labeled these questions and placed them in a roster of unique learning goals.

Bloom’s Taxonomy: Each is a different category of learning goals needing distinct kinds of cognitive thinking. The goal is to –

- Remember

- Understand

- Apply

- Analyze

- Evaluate

- Create.

These goals are not sequential as in a continuum. The first two goals – remembering and understanding are goals for creating background knowledge – necessary for all learning to follow. Later learning builds upon the breadth and depth of a child’s foundational background knowledge. This tells us why children in the primary grades receive extensive direct instruction in reading, ELA, math, science, and social studies. And why direct instruction of required information fills the first chapters and units of middle school and high school instruction. Knowing things is necessary for the later goals of thinking about and working with that knowledge.

To build the goal of remembering, teachers use questions like –

- Identification – What is the capital of Wisconsin? Of France?

- Definition – What is the meaning of the word precipitation?

- Listing – List the three branches of the US federal government?

- Recall – When did the Civil War take place? When did the first man walk on the moon?

- Recognition – Which of these formulas is correct for the area of a square?

The work of identifying, defining, listing, recalling, and recognizing words expands a child’s working vocabulary in their seeing, hearing, writing, speaking, and imaging more new words. Each question requires a child to write or speak a word in a different way that builds memory. Five to seven uses of the word reinforce short-term memory, and 15 to 17 different uses reinforce long-term memory.

Parallel to remembering words is understanding – the ways that people talk about and use words. The traditional model for remembering and then understanding is to “Say the word, spell the word, and use the word in a sentence.”

To build the goal of understanding, teachers use questions like –

- Classify – Tell me the kinds of animals eat meat? … eat plants?

- Describe – Describe what a Green Bay Packer would see standing in the middle of Lambeau Field just before the start of an NFL game.

- Discuss – Tell me why World War Two is labeled a world war.

- Translate – Rewrite this word problem into a mathematical equation.

Understanding requires definition of a word and opens a child to word families of synonyms, antonyms, and homonyms. Typical five-year olds have a vocabulary of 10,000 words. Once in school, their vocabulary grows by 3,000 to 5,000 words each year. The rate of vocabulary growth continues until typical high school students know about 50,000 words. The next learning goals give power the words a child knows and understands.

It is important to remember that, although application, analysis, evaluation, and synthesis goals are not sequential, a child’s experience in one will have tangential benefit to the others.

After securing children in meeting the goals of remembering and understanding, a teacher can instruct them in exploring what a person can do with the information learned. This goal is application. True application happens when children use the information or skill or rule to answer a question or solve problem they have not seen before – application requires new contexts.

To build the goal of application, teachers use questions like –

- Solving – If the hypotenuse is three, what are the lengths of the sides of the triangle.

- Stimulating – If you were an actor on stage, how would you react to applause after you deliver your lines? Or after the end of the play?

- Demonstrating – What are examples that show this rule works in the real world?

- Implementing – If you only had two tools – a scissors and a stapler – and a sheet of cardboard, show us how you would construct a box.

The goal of application is to produce something – a performance, an explanation, a diagram, or a product. A teacher can present children with a “messy” problem or a mystery that includes the words “what if.” These words invite the child to use all they know to solve, react, prove, or implement what they know and to produce something in a new situation. Often the product is an answer on a test requiring a child to consider what they know in an unanticipated word problem. In a real-world context, the ability to apply is the goal of most adult work life problems.

A different goal for learning is analysis. As the goal of application is to produce something in a new context, the goal of analysis is to dissect information looking for patterns, the relationships between parts, and hidden meanings.

To build the goal of analysis, teachers ask questions like –

- Relationships – What is the connection between global warming and the strength and patterns of hurricanes?

- Evidence – Which parts of this answer are based upon facts, and which parts are based upon opinion?

- Categorizing – How would you classify these statements as causes or outcomes from the American Revolution?

- Deconstructing – Separate this poem into its elements.

Analysis teaches children to be critical thinkers and to question and inquire into the nature of information. Teachers show children how to use charts, diagrams, and tables to show, organize, and rationalize similarities and differences. Children think and reason like historians and scientists. They study an event for its underlying causes and later effects. They guess how the absence of an underlying cause or sparking event may have changed history. Children chart and map chemical reactions to understand how elements relate and react to each other. They chart and map climatic events to understand forecasting. As application creates products, analysis dissects information into its critical attributes.

Educators gave an acronym to Bloom’s categorization of analysis, evaluation, and synthesis goals. They ar labeled as HOTS – higher order thinking skills. Ironically, HOTS should be the dominant goals of secondary education, but the curricular calendar relegates them to specific upper-level courses and a fraction of the school year. Best practice is for children at all grade levels, even 4K-primary, to be given goals in evaluative thinking. Teachers give children a rule or a “yardstick” and ask them to make a evaluation of information. For example, “Our rules say that you will quietly form a single file line when it’s time to come into the building after outdoor recess. What kind of behaviors would not be appropriate for your being “quiet” and in a “single file line?” Young children can do analysis.

Evaluation is making a critical judgment based upon evidence. The key to teaching children to evaluate is giving them a rule or a measurement against which they can make a judgment and provide evidence to support their decision.

To build the goal of evaluation, teachers ask questions like –

- Judging – Based on First Amendments Rights, should this writer be banned from publishing opinions in the local newspaper?

- Defending – Do you agree with the historical proposition that a “man’s home is his castle” and justifies the use of deadly force?

- Prioritizing – Given that your school has limited finances, which of these curricular programs should be exempted from budget reductions?

- Critiquing – Looking at the past list of Booker Award winners, which of these books has the best likelihood of winning the next award?

Evaluation requires understanding and analysis. Evaluation is not asking for opinions. “Do you like this abstract drawing of a barnyard?” asks for an opinion. Saying “This is an abstract painting of a barnyard. How and how well has the painter used elements of abstraction to tell you the subject of the painting is a barnyard?” asks for judgment with supporting evidence. To make this judgment, children must first understand the vocabulary of art. They must understand the definition of abstract art, and they must understand the critical attributes of abstraction. Then, they must be able to examine and dissect a piece of art by identifying the specific attributes of abstraction exhibited in the art. Finally, they must put their judgment and evidence in a coherent explanation. This is HOTS.

An evaluative assignment takes more time to prepare, more time and consideration for children to complete, and significant time for a teacher to assess and respond to a child’s supported judgment. In addition, every child may make a valid judgment with differing evidence resulting in all children succeeding in an assignment that took a lot of time. And this explains why children have limited lessons pursuing the goal of evaluation. HOTS take time and the curricular calendar has limited time.

The goal of creating also requires assimilation of other learning goals. Creation requires children to examine their knowledge of information, their analysis of critical attributes, and their evaluation of the qualities of what needs to be created to engage in creation. Creating is not just applying in a new situation but the making of something new from what is known to fit a given situation. Creating also is using evaluation to determine the “best” elements for the new creation.

To build the goal of creating, teachers ask questions like –

- Design – Design a family home for five persons that would survive fire, hurricane, and criminal intrusion. The home will be in California or South Carolina near the ocean and surrounded by woods. You are not limited by cost or material selection.

- Construct – Given toothpicks and a bottle of Elmer’s Glue, build a bridge that will support a five-pound weight.

- Reorganize – How would you reorganize the baseball, softball, football, and soccer fields on our campus to require 20% less square feet of area?

- Develop – Create a story board depicting how five children stranded on an island would create rules for their survival until they could be rescued one week later.

Lessons requiring the goal of creation attach easily to STEM curriculum, technology education, and career development. They also are precursors to real world applications of school-based education.

The Big Duh!

Benjamin Bloom gave us a structure for teaching children to develop different kinds of thinking, of cognition. His taxonomy is a scaffold we can use to ensure that all children learn more than just a recall of information. Using his scaffold of goals, we can cause children to “think and do”. Bloom is worth remembering and his theory of learning goals is a tool for optimizing every child’s education.

I encourage and challenge every teacher to analyze and evaluate their annual curriculum to ensure the teaching of HOTS at all grade levels and in all subjects.